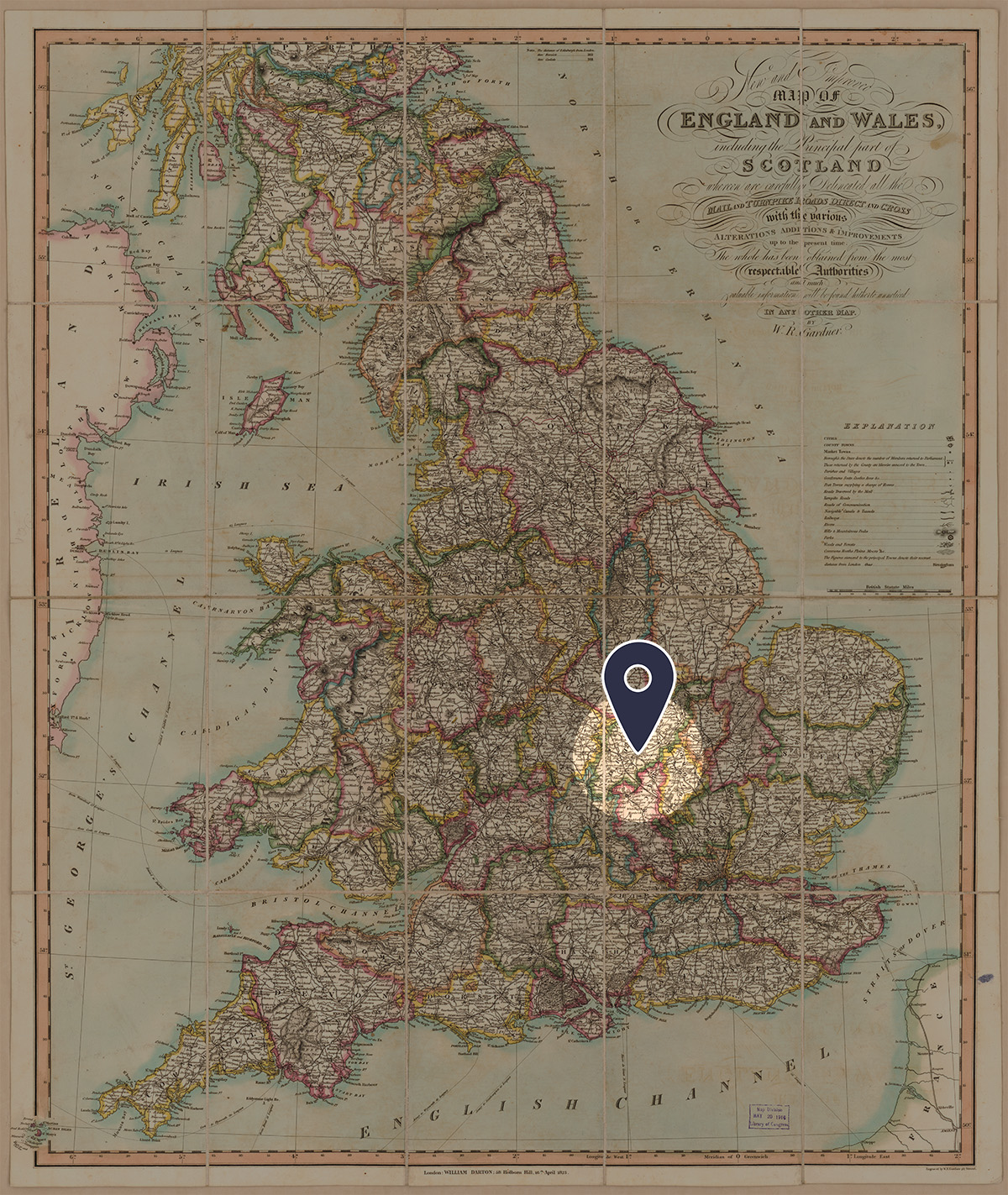

The market town of Northampton on the River Nene had been rebuilt with handsome stone buildings and wide streets following a devastating fire in 1675, and was notable for its wide potwalloper franchise. Indeed, two thirds of resident males were eligible to vote in parliamentary elections. By 1831, around 2400 people (15.6%) of Northampton’s population were qualified to vote. Northampton’s economy revolved around leather, alongside boot and shoemaking. Thomas Fuller wrote that, ‘the town of Northampton may be said to stand chiefly on other men’s legs; where (if not the best) the most and cheapest boots and stockings are bought in England’. Around 24% of adult males were shoemakers in the town in 1818, growing to 34% by 1831. The shoemakers also formed part of a larger population of Dissenters in Northampton who mainly tended to vote for Whig candidates. In the early nineteenth century, Northampton’s industrial character expanded, as iron foundries and brickworks were then founded in and around the town.

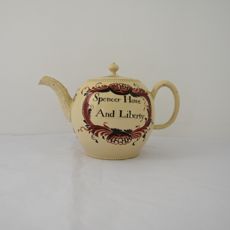

Representation for the borough revolved between Northampton’s gentry families, as well as family members of the Montagus of Horton, the Earls of Halifax. The Earls of Halifax shared influence with the Tory-leaning Earls of Northampton of nearby Castle Ashby, who served as recorder for parliamentary elections. The Earl of Halifax supported the corporation, whose mayor and bailiffs served as returning officers during elections. The general election of 1768 was the notable ‘contest of the three earls’, which occurred on the entry of Lord Spencer of Althorp to Northampton politics, who endeavoured to break the influence held by Halifax-Northampton alliance. From 1768 onwards, the Earls Spencer maintained their interest in the borough, sending out election agents and canvassing for their candidates through to the 1830s. The 1832 Reform Act made no change to Northampton’s franchise or boundaries.

340 Letter to the Mayor of Northampton 1796_1.jpg/square/230,230/0/default.jpg)

338 Handbill.pdf/square/230,230/0/default.jpg)

342 Handbill.pdf/square/230,230/0/default.jpg)

1234 Election song.pdf/square/230,230/0/default.jpg)